Does my child need a tutor?

When is it okay to use a tutor?

Whether it’s to prepare for an exam, plug a learning gap or boost a problem area, a clear objective is key to ensuring you don’t get a tutor unnecessarily. If you’re not really sure why you’re getting a tutor, chances are you don’t need one at all.

People often use a tutor:

In year 3 to ensure a child is up to speed for prep school assessments

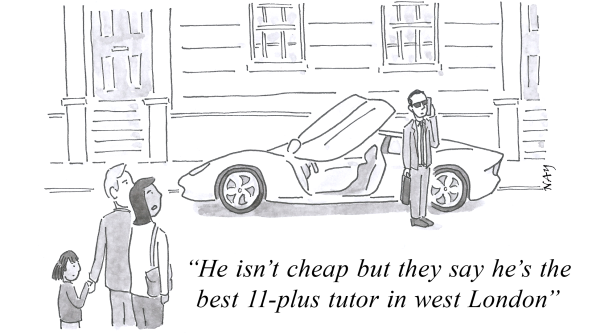

In year 5/6 to prepare a child for entry, at 11+, to the local grammar school or selective independent school. Most grammar schools (and some independents) test verbal and non-verbal reasoning, as well as maths and English

In year 6 to bolster basic maths or English competence ahead of KS2 examinations

To assist with Common Entrance subjects - perhaps to ease the anguish of algebra or Latin

To shed light on a tricky GCSE topic

To ensure A level grades are a match for UCAS offers

To improve schoolwork following a dip in grades on a school report

To get a youngster back on track after a dodgy exam result

Following a bout of illness or unexpected family set-back.

When a specific learning difficulty is suspected or diagnosed.

If your child needs extra support outside of school, our education consultants can help you find the best tutoring options for your child.

And when does your child not need a tutor?

Schools do not ‘test’ children under 5 – they may look at how they interact with adults and with other children, whether they can concentrate, whether they enjoy playing or listening to a story, but tutoring a child of this age is nonsense and you should be suspicious of those who offer it.

We are also sceptical of those who offer excessive coaching in verbal and non-verbal reasoning, which are specifically aimed at testing raw potential. Test papers are available online and it is usually sufficient to give your child plenty of practice while gradually encouraging her to up her speed – although a few familiarisation sessions may help children who have never seen them before. If a child has real problems with these papers, you are probably wise to have him or her assessed by an educational psychologist.

Parents often get inadvertently caught up in a tutoring frenzy that sweeps through their school or neighbourhood. Upon hearing other parents at the school gates discussing tutors as though they are de rigour, they snap one up themselves – without really assessing if it’s needed or could be detrimental.

Indeed, study upon study shows how important play, fun and free time are to children’s educational development. In many cases, a drop in academic standards is a sign of exhaustion and lack of downtime. Overworking children will soon backfire.

You might be surprised how much you can improve your child’s academic performance by simple measures like regular bedtimes and mealtimes and turning off screens an hour before bed – children can’t work well if they’re either tired or hungry. Read with your children and put time aside for a few maths problems here and there.

Featured in: Tutoring essentials